GARY HOBBS (Former Southern Area middleweight champion)

Things, as they say, are not always as they seem. Although former Southern Area Middleweight Champion, Gary Hobbs, was born in London, he actually considers himself to be an American. “My dad was American and my mum was English. I was born in Stepney in September 1956, and then we moved to America until I was seven. My dad was in the American Air Force, so we moved all over the place. Then my dad got stationed at West Ruislip, so we came back to England. My dad went to Vietnam in about 1968 and, when he went back there for a second term, I never saw him again after that. Him and my mum separated. The thing was, I didn’t really know him because he was always away on an American airbase, so I only used to see him maybe once a week. But it’s true that I do still consider myself to be American and I’ve got an American passport.”

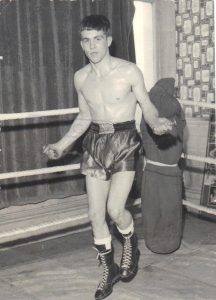

“Me and my mum lived near Harry Holland, and he took me to the Southall British Legion Boxing Club when I was 12. The other trainer there was Colin Cracknell. I was 13 when I had my first amateur fight. It was a boy from St Pancras, and I still remember his name. It was Skelton. I remember my friend got a trophy for his first fight. So I won by third round stoppage in my first fight, and they gave me a Pyrex dish! It’s really disappointing when you’re expecting a trophy and they give you a Pyrex dish. When I got to be about 14 years old, I used to stay the night at Harry’s house and look after his kids while he went out on a Saturday night. I was like his babysitter, and then I’d go to the gym with him on Sunday mornings, and I used to help him out in the corner sometimes on the shows.”

“I had 85 amateur fights, and I won about 60. I won the South West London ABAs at middleweight, and I think I got to the semi-finals of the NABCs. In my last amateur fight, I fought Jimmy Price. Harry paid him loads of money to come to London to fight me and I lost on a split decision. Jimmy Price went onto win the Commonwealth Games and, when he was getting ready for the European Championships, I went to Crystal Palace to spar with him.”

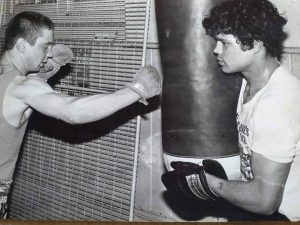

“I used to do a lot of sparring with people. I sparred with Alan Minter when he fought for the World Title against Vito Antuofermo. I was still only an amateur then, and I couldn’t believe that Alan was using me as a sparring partner. Obviously, we weren’t allowed to spar with the pros, so the thing was you weren’t meant to tell anybody what you were doing. One day, we’d gone to the Wellington Pub gym and Frankie Lucas was in there. He was the Southern Area middleweight champion at the time, and he wanted to spar with me. So I said ‘I can’t spar today because I’m fighting in another couple of days.’ Anyway, I was fighting on a London versus Ireland dinner show and I stopped the Irish Champion in the first round, and Frankie Lucas was the guest of honour. So he comes up to me and he’s shouting ‘You’ll have to come down and spar with me!’ Harry Holland was going mad, because all the ABA officials were there.”

“I never took money for sparring. Alan Minter offered me money, but I never took it. When I was a pro, I went and sparred with Tony Sibson and I wouldn’t even have thought of asking for money. I was happy to spar with them, because you’re going to learn from someone who’s better than you. When I was a bit younger, I sparred with Kevin Finnegan at the Craven Arms. The one I used to spar with regular was Keith Bristol, a good light-heavyweight who fought Denis Andries three times. He didn’t ask me for money and I never asked him. I’ve never seen Keith to this day. I always ask, and some people say he’s still about.”

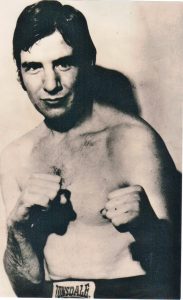

“I had my first professional fight in November 1981. They took me down to Southend and I stopped Casey McAllum in the fifth round. I suppose I was a bit nervous, but I knew I always hit hard. I was a good body puncher and I used to think to myself ‘As long as I can hit anybody, I’m in with a chance.’ So I wasn’t bothered about anybody. Boxing was just a great time and I enjoyed every minute of it. In any fight I was ever in, I never got hurt by anybody. I loved the training side of it. On Sunday mornings, we used to go running over Cranford Park. If you were a useless runner, you went first, and I used to start off first because I wasn’t very good. So I used to cheat. I used to wade across the river and get to the other side and meet them right up in the front. They’d still all come tearing past me, and I’d be soaking wet from wading through the river up to my waist.”

“The first time I went the distance was against Russell Humphreys. I beat him on points over six rounds on a show that Pat Brogan promoted in some club in Burslem, Staffordshire. That was a hard fight, and it was a strange old day actually. For one reason or another, I’d had a lot to eat and I thought I might be a bit tight on the weight. When we got there, Ernie Fossey was doing the weighing in. So, as I’m getting on the scales, Ernie came up behind me and he said ‘Stick your elbows out.’ The official in charge said ‘Ernie, what are you doing? I can see you!’ Anyway, I weighed in and my weight was all right. So that was against Russell Humphreys and I won nobbins there. I think we got £62.”

“The worst one was Joe Jackson. The gloves that we fought with were terrible. They didn’t have any 8oz gloves, so we ended up wearing 6oz gloves. They were damp, they smelt of mildew and they had no padding in them. I’d never been cut before that, and I got cut to pieces in that fight, but I still won it. Nowadays, they wouldn’t even let you wear gloves like that. They must have been about 25 years old.”

“I fought Deano Wallace twice. I beat him the first time, and he said to me ‘You was lucky.’ So we had the fight again a couple of months later and I knocked him out then. As I got out of the ring, Frank Warren said ‘Do you want to fight for the Southern Area Title against Dave Armstrong?’ I didn’t think I was ready for it, because I’d only had seven fights. But I had nothing to lose, so I just took it and that was it.”

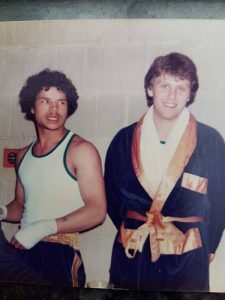

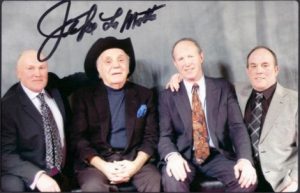

Gary and Dave Armstrong with Gary’s Southern Area title belt.

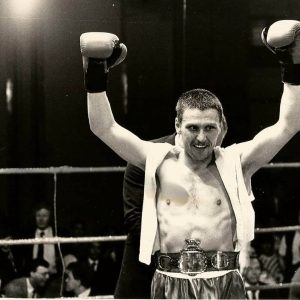

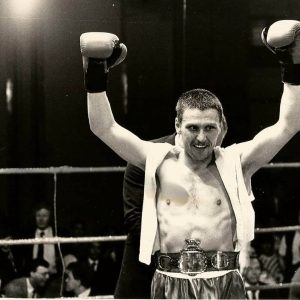

Gary won the Southern Area Middleweight Title from Dave Armstrong of Hackney in May 1983 at the Bloomsbury Crest Hotel, and it took him 2 minutes and 50 seconds to get the job done. “For most of my pro career, Johnny Bloomfield had been in my corner, and he kept saying ‘Keep your chin down and your hands up and, once he’s blown himself out, you’ve got him.’ I knew Dave was going to come out going berserk. I just stood there and took everything he threw, blocked it all and kept my chin down. I remember hitting him round the side and you could see on the television that it hurt him. Then, after that, it was easy. He slowed down then, and I stopped him. It was a great night. All my friends were all there, and I couldn’t believe I’d done it. I remember leaving the Bloomsbury Crest, getting into a coach, going to a pub at midnight, and suddenly Sports Special came on the TV with Brian Moore and they put my fight on. So I stood in the pub and watched myself winning the title on the telly.”

“I boxed Mick Morris at the Civic Hall in Solihull in October 1983, and I stopped him in the seventh round. One of the things I remember about that fight is, in the corner after the sixth round, Harry Holland and Johnny Bloomfield, the pair of them laying into me, and I mean physically! They both gave me a slap and Johnny was saying ‘You’re going to throw your career away if you don’t do something here.’ So I went out and stopped Mick Morris then, because I wasn’t going back to the corner to take another pasting from them two! Afterwards, Mick Morris said ‘I was winning that.’ I said ‘Yeah, you probably was, but you didn’t win it though, did you?’ because I knocked him out. That was the last fight I ever had.”

“What happened was I had a car accident and the aerial went in my eye, and that was it. It was the end of my boxing career and it happened overnight. They took me to the eye hospital and they said ‘Sorry, you’re blind in one eye.’ Then a friend of mine, Bob Flynn, told me ‘I’m going to take you to Harley Street,’ and he took me to see a specialist up there who said they may be able to save the sight in the eye if I had the operation that day. They booked me into the Harley Street clinic. An eye surgeon came down. I had the operation, and they stuck me in a lovely hospital for recovery overnight. Norman Tebbit, the MP, when his wife had been in the Brighton bombing, she was in the next room to me, so it was a nice place and Bob Flynn paid for everything. Then I woke up the next morning and they said to me ‘No, that’s it.’ I was only 28, and I was completely blind in my right eye. But Bob Flynn really looked after me, and I still see him today. I go round his house every Christmas.”

“When it was over, I just had to get on with life really. After I done my eye, I never put a pair of gloves on again. My career ended that day, and that’s the end of it. I’ve got three children, Kevin, Colin and Lisa, and you have to do whatever you have to do to look after your family. You’ve just got to get on with it. It was Chris Finnegan who told me that. I met up with him at a boxing show one time and we had a chat about it, because he was blind in one eye as well, and that’s what he said to me, “You’ve just got to get on with it”, and I didn’t think you could get much better advice than that. I had an HGV licence and, because I lost my eye, I had to go before the court and prove that I could still drive a lorry. So I went and done that, and started driving a lorry round Europe then with one eye.”

For some years, Gary has been a regular face at the London Ex Boxers Association, and he has proved to be an asset to the organisation. He is like a magnet for attracting new blood into the meetings, spreading the word and bringing along many of his contemporaries from the past. They are a lively bunch who are growing in number every month, and the old guard, of which there are hundreds, are delighted to have them in their presence. “Tony Rabbetts told me to come to LEBA a few years ago, and I’ve been attending ever since then. I really enjoy it there, and I’ve met a load of people that I haven’t seen for years. One time, I bumped into Dave Armstrong up there, who I won the Southern Area title from. The funny thing was, he was standing right near me and I didn’t even recognise him at first. A few years ago, somebody told me that I was entitled to have a Southern Area Belt because I wasn’t able to defend mine. Anyway, Ray Caulfield, the secretary of LEBA, contacted the Board of Control and they organised a belt for me, which they presented to me at one of our Sunday morning meetings. Dave came along that day as well, which was great, and it was a very proud moment for me to finally get my belt to keep after all these years.”

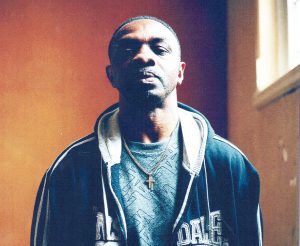

Gary with old stablemates, Tony Rabbetts and Rocky Kelly, having beer and banter at LEBA.