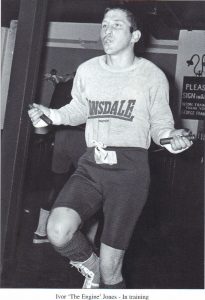

Ivor ‘The Engine’ Jones

Ivor ‘The Engine’ Jones is a decent, law abiding citizen. He’s never been in trouble with the police in his life. However, in the days when he took centre stage in the ring, if they had made stealing the show a criminal offence, Ivor would have been up there with Britain’s most wanted. Be it at York Hall or the Albert Hall, Ivor rarely took a backward step from the first bell to the last, and his drawing power was phenomenal. His family and friends travelled from North Wales in their coachloads, the Newmarket racing crowd came to support him en masse, a throwback from his days as an apprentice jockey, and he rapidly built up a staunch army of devotees from London, where he made his home in 1979. In a sport where selling tickets plays such a crucial part, this quiet man of boxing and his barmy army of fans were every promoter’s wildest dream – although perhaps with the exception of the night when he came in on the wrong end of a close decision in the ABAs, and his followers became so irate that they send a pool table flying out of the window!

Born in Holyhead on 8th April 1954, Ivor comes from the most solid and supportive family. “My dad’s name is William, my mum’s name is Elizabeth, and I’ve got two brothers, Colin and Robert, and one sister, Sharon. My dad was the coxswain and the pilot on the Holyhead Lifeboat for about 30 years. When my dad used to go out to sea, I didn’t really understand the danger he was in, to be honest, because I was too young to realize. But I remember my mother used to sit up at night worried sick, listening to the radio in case there was any news. When my dad was on the lifeboat, he was awarded a silver medal and two bronze medals for saving people. My dad is 90 years old now, and he’s always supported me in whatever I’ve wanted to do. We’re best friends, and we get on absolutely brilliant. That’s meant a hell of a lot to me over the years, as it would to anybody, I should think. My Uncle Llewellyn Jones boxed as a professional. He’s passed away now, but, when I boxed, he used to follow me everywhere. He loved coming to see me, and he was there every time. He was all ‘Ivor this’ and ‘Ivor that’ and he supported me like anything, being an old pro himself.”

“I was working when I was 12 years old. I done paper rounds and everything like that, but labouring on the building sites was my first job. Then I left home at 15 to become an apprentice jockey at Newmarket for the trainers, Fred and Robert Armstrong. I was at Newmarket for five years, and I enjoyed it. I never had any races, but I went out on the gallops all the time and it was brilliant, fantastic! I rode with some of the best jockeys in the world, like Lester Piggott, Brian Taylor and Willie Carson. There were loads. We didn’t really get to know them. We just used to say little things about the horses, but that was it really. Then, about 25 years ago, I was working in London and I was looking after a big house in Victoria, and who knocked at the door? Lester Piggott. I couldn’t believe it! I was just looking after the house and he’d come to meet the owner. He didn’t recognise me, but I knew who he was obviously, so we had a nice little chat then.”

Aside from the racing, as did many of the stable lads, Ivor also enjoyed boxing. He was 17 when he first met his then-to-be trainer, Colin Lake, and theirs was a friendship that has lasted to this day. “I was in my teens when I met Lakey for the first time. All the lads used to spar in the loft at the Exeter House Stables. There was an old ring in there, and we used to have to sweep up the straw first. We used to have wars and I was useless really, but Lakey was coming up there watching and he said he could see a bit of potential in me.”

The bond was formed, and Ivor became one of Colin Lake’s protégés. As an amateur, Ivor won the prestigious National Stable Lads Championship three times. “Winning the Stable Lads was very important, definitely, not just for me and Lakey, but for the Armstrongs as well. So it was good for everybody, and I got a big picture in Sporting Life. But I was always going to turn pro. So, in 1979, Lakey brought me to North London. I stayed with Lakey for a while, and then I got a flat.”

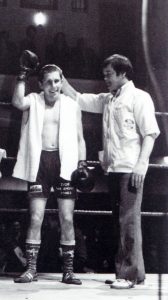

That’s my boy (Ivor with his trusted trainer, Colin Lake)

In October 1979, Ivor made his professional debut against Carl Gaynor at the Lewisham Concert Hall. “When I turned professional, I had to go for my medical and this doctor was trying to find my reflexes. He kept hitting me on my knee with a hammer and nothing was happening. In the end, I was getting fed up, so I just kicked my leg out. He said ‘I knew I’d find his reflexes,’ but he didn’t find nothing. I’d just had enough of him hitting me with his hammer! When I came out to fight Carl Gaynor, I felt great. I really wanted it. Carl was a nice little boxer, but I was so confident and I stopped him in the third round. I loved being a boxer. I loved the discipline it gave me, and I only cared about winning. I would have fought for nothing, to be honest. If I’m going to do something, I’m going to win.”

“I had some decisions that went against me that I definitely didn’t agree with. To tell you the truth, the same thing happened to me in the amateurs. I fought the best and I knew I beat them, but that’s what boxing can be like. It’s all politics and promises. I beat Robert Hepburn on points in my fourth professional fight. But, when I boxed him in the amateurs, in the ABA quarterfinals, I knocked him down five times in three rounds, and they gave him the decision. The crowd didn’t like it and there was a riot. That was at the Cambridge Leisure Centre, and the pool table went right out the window! I think all the later fights were put off, they went right into one, but I wasn’t even thinking about any of that. I was mad because I didn’t get the decision, and that was all I could think about.”

“In the pros, I boxed John Dorey twice, both times at York Hall. Me and John used to spar nearly every single day up the Thomas A’Becket and we were good friends. But, when it comes to boxing, it’s business.” The Engine was firing on all cylinders for both of his fights with the Eltham man. The first time, in September 1982, Ivor beat Dorey by half a point, and the pair of them received a standing ovation, together with a generous cascade of nobbins. They fought again the following March, this time for the vacant Southern Area bantamweight Tttle. It proved to be another blazing battle and, this time, when the referee raised Dorey’s glove at the end, Ivor could only stand bewildered in his own corner. “You see, for me, the Southern Area Tttle was going to be a steppingstone. It was a starting point. I was looking much further ahead than that and, when the referee raised Dorey’s hand, I couldn’t believe it. I believe I won the second one easier than the first one.”

“One of my favourite fights was when I stopped Kelvin Smart at the Albert Hall. Frank Bruno was top of the bill that night, and me and Bruno shared the same dressing room. I think Bruno knocked his man out in three, and I stopped Kelvin Smart in two. I got him with my favourite shot, my left hook to the body, and I really wanted that win, because do you know what he said? The referee called us to the middle of the ring before we started boxing and, as we touched gloves, Kelvin Smart said to me ‘You Welsh bastard!’ I wouldn’t mind, but, when he won the British Title, I went and congratulated him and shook his hand. So I knocked him down the first time and he jumped back up, but I think that was just reflexes. So then I had to knock him down again. My Uncle Llewellyn had just died before that fight, so, after I’d won, I grabbed the microphone and I done a speech at the Albert Hall. I dedicated that fight to my Uncle Llewellyn.”

The Engine pulled into his final station in December 1985, when he lost a points decision to Shane Sylvester on a National Sporting Club dinner show. “I already knew that it was gone by then. The spark had gone away, and I knew I wasn’t the same fighter. I never told Lakey at the time, because I knew he would have pulled me out and I didn’t want that. But, after that fight, Lakey knew and he said ‘Right, you’re never fighting again,’ and I respected his decision, because, to me, Lakey is the best trainer in the world. He’s my best friend. We’ll argue. It don’t matter where we are, and we’ll argue. But everything I’ve learned has been off Lakey. When he trains a fighter, he gives everything. He did it with me, he did it with Colin Dunne, and I’ll always stick up for Lakey, no matter what.”

“The thing was, I was working all the time during my boxing career, on the roofing mostly, and the only regret I’ve got when I look back is that I should have packed work in really. I knew I needed a few quid to live on, but I should have roughed it a bit more, so I could have concentrated more on the boxing. I think, for any professional boxer, it is hard when you retire. You don’t know what to do. Some people go drinking. But I was lucky, because I went straight into training. I started working with Lakey down the Angel ABC, and we’re still doing that to this day.”

Ivor and Lakey enjoying a pint after training the lads down the Angel ABC in Islington

On the face of it, Ivor’s demeanour is quiet, a trait that some mistake for shyness. But, give him half a chance and, in what he deems to be the right circumstances, he’ll give you a glimpse of his mischievous sense of humour. Along with Colin Lake, he is still very much a regular face on the ex-boxers circuit, and Lakey’s feelings for his longstanding pal came through loud and clear when I asked him for a quote to finish off this piece: “When Ivor was boxing, he fought the best, and you wouldn’t want him in front of you, I’ll tell you that. I’ve worked with some great fighters, and Ivor is one of them. All these years, he’s worked with me training the lads at the Angel, and I wouldn’t have been able to do it without Ivor. It would be too hard. Me and him are the same. One minute we’re arguing, and the next minute we’re laughing, but I’ll tell you this. Ivor is like a son to me, and I think the world of him.”