I interviewed Alan almost 20 years ago for my first volume of Sweet Fighting Man. We had so much fun that day, and I will never forget the waiters in the restaurant closing the doors at the end of the lunchtime session and allowing us to stay and finish our conversation. Alan was over the moon with his chapter. He used to tell people that I was “the best boxing writer in Europe,” which always made me smile. Now that he has passed away, it feels right to share his beautiful words one last time. Rest easy Champ. It was a pleasure to know you.

***

“He wants looking after sometimes. You’d have to nail him to the floor to beat him, know what I mean? Alan could go on to be one of the greatest fighters we’ve ever had. The boy’s something special.” (Doug Bidwell)

ABA champion and Olympic bronze medallist, British champion and outright owner of a Lonsdale Belt, European champion, and finally undisputed middleweight champion of the world, Alan Minter was indeed “something special”.

I arranged to meet Alan for this interview at Bertorelli’s in Covent Garden. It was a crisp and sunny October afternoon and, while I waited in the nearby square watching an exquisite mime artist who was made up like a porcelain statue, I suddenly sensed that someone was watching me and there, smiling from across the crowd, was Alan. I walked over and we stood quietly for a few moments before he said “Just down there, you’ve got the Opera House. There’s a really beautiful dome inside, but years ago it started coming apart. I had a plastering company and we got the contract for it, so we went in there and put it right.” I replied, “Oh, and which bits did you do, the cupboards?” The reason for my audacity will become obvious as this story unfolds, but, suffice to say, I received a sharp look from Mr Minter as if to say “I see somebody has been doing her homework, madam!”

Alan’s eyes are a clear, piercing blue. Every now and then, they light up as he flashes the disarming grin which must have got him out of a fair bit of trouble over the years. As we made ourselves comfortable in the restaurant and I began to ask him about his career, those eyes were not looking for any escape routes. For some reason, his brutal honesty, particularly about what he saw as his own shortcomings, took me by surprise. Before he answered certain questions, he became thoughtful almost to the point of being distant, but then the blue eyes became focused and the stories flowed.

Alan was born in Penge on 17 August 1951. He spent the first two weeks of his life in an incubator. “Yes, I was dying. I had my last rites read to me and everything. They got the vicar in and they said ‘He won’t survive. He won’t come through.’” His father was a Londoner called Sydney and his mother, Annalisa, was from Germany. They met while Sydney was doing his national service, and they were both supportive of Alan’s boxing ambition. “I remember when I’ve gone home after boxing with black eyes, all banged up, and my mother has cried her eyes out, but she never once said to me ‘You don’t want to do that.’ She never said nothing.”

Alan, who boxed as a southpaw, initially discovered boxing at the Sarah Robinson School in Crawley. “I was always in trouble. I spent most of my time being put outside the classroom. Then one day my PE master, Mr Hansom, bless him, asked me to get a boxing team together to represent the school. Anyway, we all got beat, and that was when I joined Crawley ABC and I lost seven fights in a row. I boxed on a Tuesday, so I’d never go to school on a Wednesday because the kids would say ‘You got beat.’ One day, I’m in school on a Wednesday, in assembly, and the headmaster’s come on the stage and he’s gone ‘Well, well, he’s in school for the first Wednesday in many, many weeks. He must have won his first fight. Alan Minter, stand up.’ So I stood up and the whole school applauded and cheered. It had never happened to me before, but it happened then, and that was it. That’s what made me carry on. I’ve always sad it’s sad for children who are doing something and they don’t get a pat on the back. Mr Hansom has written to me since, not recently, but when I achieved what I achieved. I sometimes wonder if he’s still alive.”

Alan left school at the age of 14 to work in his father’s plastering business, but unfortunately plastering wasn’t really his bag and he rapidly found himself relegated to the cramped world of cupboards. Hence, the reason for my earlier impertinence. He confirmed “For years, I was known as ‘The Shoe Cupboard Kid’. I was in the cupboards for years! But, see, a lot of plasterers, when they’re doing cupboards, they aren’t bothered, but my cupboards were spot on!”

It was at Crawley boxing club that Alan met Doug Bidwell, who became a major force in his boxing life and eventually his father-in-law. “Doug was the competition secretary at Crawley and, as I progressed as an amateur, he became my trainer. We stayed together all through my boxing career, amateur and pro.” Tucked firmly under Bidwell’s wing, Alan’s boxing skills blossomed and, in February 1970, he was selected for the England training squad, which involved spending a weekend every month at Crystal Palace training centre under the watchful eye of national coach, David James. “David James was very much like a headmaster. We were young, we were boisterous and we didn’t really want to listen to what he was saying. But the thing was with him, although he had never had a glove on in his life, what he said was spot on. Everything he told you to do was 100 per cent right. He was like Doug Bidwell, in the sense that, if Doug told you to do something, you’d do it and it worked. There is the trust. There is the belief in the guy.”

One of the pranks that used to drive David James to distraction was the night-time escape committee, headed up by Alan, John Conteh and Larry Paul. Every Saturday night, they would diligently plan their breakout via the fire escape and head for the Crystal Palace Hotel. “Yeah, we used to sneak out and have a drink, and it was nice. But we did train hard, honestly. They got us on a Friday and a Saturday and, by the time we left Sunday lunchtime, we couldn’t walk! So a few pints of light and bitter at the Crystal Palace Hotel, it was beautiful.”

It was in May 1970 when Alan was christened with his ring-name of ‘Boom Boom’. He was representing England at the Multi-Nations tournament in Holland, and he was boxing in the first leg against Peter Lloyd of Wales. “See, I used to make this grunting noise when I threw a punch and the referee kept warning me, ‘Don’t make that noise. You’re making the noise again. If you keep making that noise, I’ll disqualify you.’ But it was a habit and, even if I didn’t throw a punch, the noise was still coming out! Whenever I was boxing after the warnings fight, as I would climb into the ring, all the crowd would shout ‘Boom Boom!’ and it was lovely. I ended up winning the Multi-Nations silver medal and, after all the warnings and everything, I got the trophy for best boxer of the whole tournament.”

Alan boxed 30 times for England, winning 25, but the blue eyes were firmly focused on the 1972 Munich Olympics. “It was funny, because I’ve got to the Olympics and I’m still working for my dad’s plastering company, still in the cupboards! So my dad’s come round to the site to tell me that I’ve had a letter to say I’ve been picked for the Olympics and he couldn’t find me because he didn’t know which fuckin’ cupboard I was in! When he did manage to find me, the whole site closed down. Everyone got booze in and we had a party because I had just been picked to represent my country.”

“We went out to Munich and I had my 21st birthday out there. All the trainers and everything, we all went out for the night and it was brilliant. When we got back to the Olympic Village, we couldn’t get back in. All the doors and gates were locked. The security was phenomenal. There was helicopters, guys with machineguns, and we couldn’t get near. There had been a terrorist attack. There had been a massacre, and all the Israelis were killed.”

In his first fight of the games, Alan stopped Reggie Ford of Ghana in the second round. His next opponent was Valery Tregubov, a Russian southpaw who was twice European champion and nine years older. “Tregubov was the only one I was worried about. I had respect for his reputation. He was a good fighter and he was powerful. He would walk through anyone, and I couldn’t sleep at nights. I knew they’d drew me against him, and I was worried. Anyway, I nicked it on points and, from that day forth, it was very difficult to get motivated because he was the most dangerous man there in my weight class and I beat him. So I couldn’t get no butterflies or nerves boxing anyone else.”

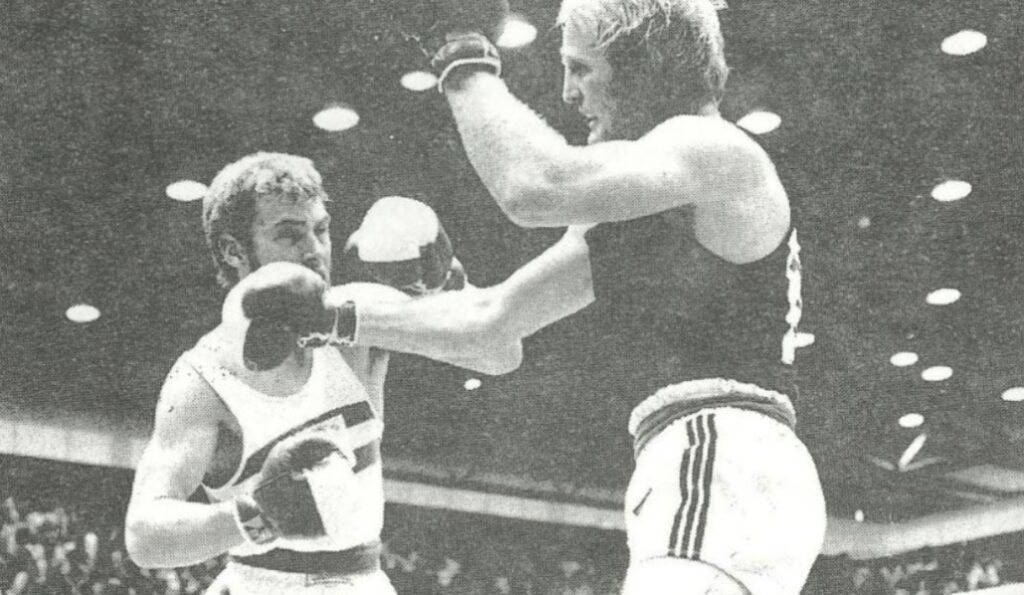

Next came the quarter-finals against Loucif Hamani of Algeria. The referee gave Alan three cautions and a public warning for grunting. But, aside from that, he got the verdict and he was now assured a bronze medal. His opponent in the semis was Dieter Kottysch of Hamburg, and this would be Alan’s final fight as an Olympian, and as an amateur. “He never won that fight, and the crowd knew he was beaten. I’ve seen the film since, and I can’t get over how tiny I was. I was like a little boy. I’m standing there and they announced the majority decision to him. He jumped up in the air, and I just couldn’t believe it. The crowd booed and jeered and, when they presented me with the bronze medal, the crowd erupted again because they knew! After that, I turned pro with Doug Bidwell.”

Dieter Kottysch

Alan made his professional debut on 31 October 1972 at the Albert Hall against Antiguan born Maurice Thomas of Bradford, who he stopped in six. “I was with him the other day. I’m speaking at this venue and I’m in the room before I go in and they’ve gone ‘Alan, this is Maurice Thomas.’ I’ve gone ‘Jesus Christ, Maurice! How are you?’ He’s gone ‘Alan, I’ve never told anyone that I boxed you. Nobody knows.’ So, when I finished speaking, I said ‘Before I sit down, I would just like to make a tribute to somebody I didn’t realise I would ever see again. This is the guy I fought in my first professional fight, and everyone in this room knows him so well. Gentlemen, can we have a round of applause please for the one and only Maurice Thomas?’ He looked at me and he’s stood up, and everyone was applauding and saying ‘I never knew you fought Alan Minter!’ Afterwards, all these people were going up to Maurice and asking for his autograph, and I’ve even gone up to him and said ‘Maurice, can I have your autograph?’ He said ‘I’d love to, Alan,’ and I thought that was nice.”

During the following five weeks, Alan notched up another four wins before going the distance for the first time against Pat Dwyer at the Albert Hall. “He was a good fighter, Pat Dwyer. He was tricky. You see, they’d all had more experience than me. They’re all there to test you.” In his next fight, he stopped Pat Brogan in seven at York Hall, becoming the first man to stop that durable journeyman, but not before getting cut for the first time, in the first round. “I didn’t even know I was the first man to stop him. Look, he’s there to be beaten, like I’m there to be beaten. I’m not bothered if I stop him or if I beat him on points, as long as I’ve won. And that’s probably why I’m never a guest at his promotions!”

After four more wins, Alan suffered another cut which resulted in his first defeat as a pro, when he was stopped in the eighth and final round by Scottish veteran, Don McMillan, at the Albert Hall. McMillan was down three times during the fight and Alan was well ahead on points, but his eye damage was too grim for Harry Gibbs to allow the fight to continue. “That was a bad cut. It was at least two inches long. Clash of heads. You get a clash of heads like that and someone’s going to be cut. All the cuts that happened to me, they’ve been brought on by myself. Frustration. Instead of boxing when I should have boxed, I’d be having a fight. They used to say ‘Walk in there, hit Alan Minter, and stand back and wait for him.’”

During the next year, cuts would cause major problems for Alan. He had six fights, three wins and three losses, all of the defeats coming as a result of eye damage. Two of those defeats came at the slicing fists of Jan Magdziarz, a Southampton-based Pole. In October 1974, Alan shared the ring with Magdziarz for the third time, and Harry Gibbs disqualified both boxers halfway through the fourth round. “I was frightened I’d get cut again. It was an eliminator for the middleweight championship of this country and we was both disqualified, both slung out of the ring. I’ll tell you what he had, that right hand, and it was so fast and straight that he couldn’t miss me with it. I shouldn’t have fought him. Every fighter has a bogeyman, and he was mine. He was coming forward and I went back. I was coming forward and he went back, and neither of us threw a punch. The crowd were going berserk.”

In November 1975, after a winning run of five fights, Alan had his first of three epic battles with Kevin Finnegan, the popular Battersea boy who had held the British and European titles the previous year. The prize on the line at the Empire Pool (later Wembley Arena) was the vacant British middleweight title, and the clash between these two was eagerly anticipated. “Me and my wife went to London and I wasn’t disciplined. I was in Harrods drinking milkshakes. I wasn’t even thinking about the weight. On the morning of the fight, we went to the ‘Becket and I was six pounds over the middleweight limit. Doug Bidwell done his nut! I had an hour and a half to get six pounds off. I worked and worked, skipped and skipped, and I had three plastics on me and the sweat was pouring out. I jumped back on the scales and I was bang on the 11st 6lb limit. That night, I boxed 15 rounds to become the middleweight champion of Great Britain, and I beat Kevin Finnegan by the smallest possible margin of half a point.”

After an eight round stoppage win over Trevor Francis, Alan made his first defence of his British title against Billy Knight at the Albert Hall in April 1976. As amateurs, Alan and Billy had been firm friends. “My best mate of all was Billy Knight. He and I were roommates for years and years. I went to his wedding and he came to mine, and it was beautiful. He was a lovely man. They said to me ‘How can you fight a friend? How can you defend your title against your mate?’”

“In those days, champions and former champions were introduced into the ring at boxing shows. One night before I fought him, they introduced us both. I walked down the aisle shaking everyone’s hand, and Billy walked down the aisle shaking everyone’s hand. He’s got in the ring and I’ve gone ‘All right, Bill?’ and he’s gone ‘Fuck off.’ He’s stood beside me and I thought about what he had just done in front of everyone, and I thought ‘That’s the finest think you could have ever done to me. Now you’ve got a problem!’ He was a good all-round fighter, Bill, a typical class fighter. He had fast hands, accurate punches. Doug says ‘Whatever you do, don’t let him get into a pattern. If Billy Knight gets into a pattern, you’ve got a problem. As he start’s settling down, you’ve got to break his style. Break it.’”

Alan floored Knight twice, backed him into a corner and tore into him, which prompted referee, Sid Nathan, to stop the fight right on the bell to end the second round. A jubilant Alan hugged everybody he could get hold of, including Sid Nathan. Knight subsequently needed six stitches in a cut over his right eyebrow, and his trainer, Frank Duffett, confirmed that he was going to pull him out at the end of the second round anyway. For the record, this was the quickest finish to a British title fight in almost 13 years.

A month later, Alan travelled to Germany to stop Frank Reiche in seven rounds. “Frank Reiche was so powerful. In the whole of my career, that was the best I ever boxed. That was the night when Ali boxed Richard Dunn and, after my fight, I’m at Muhammad Ali’s dressing room door and I wouldn’t knock on it. Bob Arum came round and he says ‘Do you want to go in and see him?’ I said ‘Oh, I’d love to,’ and we went in and he was laying there on the couch. I had two black eyes, and he said ‘Hey, you been fighting, man?’ I said ‘Yeah,’ and he said ‘How did you get on?’ I said ‘I won, thank you,’ and that was it.”

In September 1976, Alan made his second defence of his British title in his second fight with Kevin Finnegan at the Albert Hall. As in their first fight, Alan won the decision over 15 rounds, and the decision was, once again, by a margin of half a point. “He had me in the second one. I was bashed up in the eleventh round and in the last round. At the end of the thirteenth, my corner told me ‘You’ve got one round to go. This is the last round. Go and win it big. If you don’t win this one, we’re going nowhere.’ When the round was over, I went over to the referee to have my hand put up, and he says ‘There’s one more round to go.’ I went out for the fifteenth, and I was drained. I thought it was the end of the fight, and now I’ve got one more round to go. There was nothing there.” When the fight was over, Finnegan offered his hand to Roland Dakin, who smiled gently, shook his head and moved across to lift Alan’s glove. Alan had won his Lonsdale belt to keep.

After two more wins in 1976, in February 1977 the opportunity came to challenge Germano Valsecchi for his European title in Milan. “I was the first Englishman to beat an Italian for the European Title in over 50 years. We went over there and we had a lot of people with us from different parts of London, and I stopped him in five rounds. So I won the European title, and then I fought Ronnie ‘Mazel’ Harris, the most feared American middleweight. He won a gold medal at the Olympics, he’d been a pro for about eight years, and no one wanted to fight him. He was too dangerous. Anyway, I’ve took the fight. I saw it on film the other day, and I didn’t remember until I watched it that I was stopped sitting down in my own corner.” At the end of the eighth, Alan’s lip was split in half. The referee went to his corner and stopped the fight. Meanwhile, in the opposite corner, Harris had double vision and his jaw was broken in two places.

In July 1977, Alan travelled to France to trade leather with Emile Griffith. At the time he shared the ring with Alan, he 39 year old American had been a professional for 18 years and had boxed over 100 times. Alan won on points over ten rounds, and Griffith never boxed again. The blue eyes glowed with pride as he told me “I boxed Emile Griffith in Monte Carlo. He knew everything. He was champion of the world at welterweight, light-middle and middleweight. After the fight, I told him ‘Emile, I’m proud to have fought you.’ He said ‘Oh? Maybe we can do it again sometime.’”

Alan returned to Milan to defend his European title in his next fight against Gratien Tonna. In the sixth round, Tonna opened up a two inch cut on Alan’s forehead and he was stopped round eight. After the disappointment of losing his European title on cuts, Alan went back after the British title. Once more, it was Kevin Finnegan in the opposite corner at the Empire Pool. Once again, Alan won it by a half a point. Once again, it was close, but not so close as the others. “The third one? No, it wasn’t so close. It was more of a comfortable win. I still one it by half a point though, but it was much easier for me.” They never shared the ring again, but, in his autobiography, Alan described Kevin Finnegan as “One of the cleverest fighters I ever met, one of the toughest and classiest fighters ever to lace up a glove.”

In February 1978, Alan had his first professional fight in America. He stopped Sandy Torres in five at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas and he had a smashing time in tinsel town. But, five months later on 19 July 1978, Alan experienced every fighter’s worst nightmare. He travelled to Italy to fight Angelo Jacopucci for the now vacant European middleweight title, a belt that both had held and both had lost. As the pair stepped through the ropes at the Municipal Stadium in Bellaria, Jacopucci had lost only two of 35 fights, but he was not well respected by the Italian fight fans. They called him a coward. But, the night that Jacopucci shared the ring with Alan, he fought like a tiger. In the twelfth round of a fight that left Alan bruised and cut, three right hooks sent Jacopucci backwards and a final massive left put the Italian down. As Jacopucci lay against the ropes, he was still conscious, but he failed to beat the count. That night, the proud and brave Italian finally won the respect of his countrymen that he had craved throughout his career. He collapsed in the early hours of the following morning and he died two days later after unsuccessful brain surgery. The blue eyes were dulled by sadness as Alan explained “Anyway, he died after I boxed him. See, the Italian press were saying that he was the worst fighter they had ever produced. They geed him up and he geed himself up to prove them wrong, and he gave me a tough fight. I was marked up and everything. Afterwards, we went out for a meal and he said ‘Minter, you good fighter.’ I said ‘Thank you. I’m honoured to have fought you.’ When he sat down at the table, he was all right. I woke up the next morning and they told me that he was in a coma.”

Less than four months later, Alan defended his European title against Gratien Tonna at the Empire Pool and avenged his previous loss to the Frenchman with a six round stoppage win. “When I boxed Tonna in Italy, he came in with a massive entourage, showing his power, and he’s gone to me ‘Minter, I kill you! I kill you!’ He had me worried, because I didn’t know he’d go to the extreme of saying that.” The blue eyes turn to blazing ice. “So now I’m fighting him in London. He’s come to my country, my weigh-in, my people. Anyway, he’s come up to me at the weigh-in and he’s gone ‘Minter, how are you?’ I’ve gone ‘Fuck you! You’ve got a problem tonight.’ He’s gone ‘Minter, we friends.’ Anyway, they’ve pulled us apart and, when we got in the ring, I stopped him. He’s turned his back and thrown his arms in the air. He swallowed. He was a bully, and I’ll tell you, fight fire with fire and bully a bully.”

Later that month, Alan relinquished his European title to concentrate on securing a world title fight, but first there was other business pending. A February points win over Rudy Robles was followed in May by a nine round stoppage of Renato Garcia, who later declared “I felt like General Custer saying ‘Where are all those bloody Indians coming from?’” The following June, Alan stopped Monty Betham in two and, in October, he outpointed Doug Demmings, and finally the opportunity arrived to challenge the undisputed middleweight champion of the world.

His name was Vito Antuofermo. He was a rugged and aggressive Italian who had lived in Brooklyn. Hugh McIlvanney described the pair in The Observer as ‘Mary Poppins versus the Wolfman.’ But, when Alan climbed through the ropes at Caesars Palace on 16th March 1980, there was nothing Disney-like about his performance as he outboxed Antuofermo over 15 rough rounds. “There was a big contingent of English supporters who came over. At the end, the crowd all jumped in the ring, ‘cos, in those days, the crowd could get in the ring. As they dispersed, the bell went, ding, ding, ding, and it happened, a split decision. Anyway, the judge from Germany scores it 134 Minter, 133 Antuofermo, so I’m one up. The second judge scores it 134 Antuofermo, 133 Minter, so now we’re level. Then the third judge all the way from England, Roland Dakin, scores it 130 Antuofermo, 136 Minter, and I thought ‘That’ll fucking do me!’”

After the decision was announced, Alan dropped to his knees and cried with relief. Among the ringside crowd was a delirious Terry Downes, who had screamed at Alan throughout the fight, and Joe Louis, who declared “That Minter is one helluva good fighter!” Frank Sinatra visited the new champion’s changing room afterwards, sang ‘My Way’, and gave his hotel suite to Alan by way of congratulations. “When we got upstairs, there was no beds, there was no television, no nothing. It was an empty room he give me. So I phoned downstairs and I said ‘There’s no bed in the room!’ They said ‘Press the button.’ Then – boom! – and everything happened. A television screen came out of the wall. It was beautiful.”

“The next day, Larry Holmes was working out in the gym, and all the English people were there to watch him train. The gym was packed and, before he started, he got in the ring and he says ‘I’d just like to say to all you English people here today thanks for coming to watch me work out, but I’m proud to say you have the new undisputed middleweight champion of the world, and you tell Alan Minter, don’t wee in the street, don’t spit in the main road, do everything a world champion should do.’ With that, I’ve walked in and he said ‘Alan, congratulations!’ It was marvellous.”

The citizens of Crawley turned out in their masses to welcome their champion home. “Gatwick Airport! The crowds and the bands and the music. Ah, Christ! It was packed. It was something that I never expected, ever. The next day, I don’t know how they kept it a secret, but they picked me up, my management and my family, and they drove me through Crawley to the council depot and there was a stagecoach with four grey mares and all my family got on it. I felt totally embarrassed. As they took the stagecoach out, I’m sitting on top and there’s a few hundred lads going ‘Well done, Alan,’ and I thought ‘Well, I’m not going to sit on this stagecoach much longer, there’s no one come to see me!’ Then, as we get into Langley Green where I was brought up, there was all people. You couldn’t see a bit of grass or pavement or road. The roar! As we’ve gone through Langley Green, they were 12 deep on the pavement. They was in the road going up the hill towards the M23. Thousands! Cars were stopping. Going down the High Street, 15 deep in the road. Then, into Queen’s Square, the finale. People! Thousands and thousands of people. I’ve got photographs, and I can get out my magnifying glass and go ‘Yeah, that’s so-and-so!’ It was unbelievable.”

Less than three months later, Alan defended his world title in a rematch with Vito Antuofermo, this time at Wembley Arena. Antuofermo was cut in the first round and, by the time that fearless warrior was finally pulled out by his corner at the end of the eighth, his craggy features were a pitiful mess. “I watched it the other day, and they would never, ever have let it go on today. It should have been stopped earlier. The eighth round came, they called the doctor to have a look at the damage, and he’s let the fight go on. So the ninth round came, and his cornermen pulled him out.”

Alan was a world champion on top of his game and he was flying high, but he also needed a rest. “See, what you’ve got to remember is that, when a champion wins his title, he can bask in the glory of being champion. He can choose who he wants to defend against and make a lot of money. After I won the first fight with Antuofermo, I got a letter from the WBC and the WBA saying I had 60 days to defend against Antuofermo. So I beat him at Wembley, and then I had another 60 days to defend against the number one contender or be stripped of the title, and Marvin Hagler was the number one contender.”

On 27 September 1980, Alan defended against Hagler. The menacing switch-hitting southpaw had drawn with Antuofermo in a challenge for the world title ten months earlier. He was furious that he had been denied the decision, and he let it be known that he regarded himself as the uncrowned middleweight king. The air at Wembley was thick with tension that night, fuelled by the rumours that, during the build-up to the fight, Alan had uttered the words “I’ll never lose the title to a black man.” This quote has been documented so many times over the hears, and I asked him if he actually said those words. “Yeah, I said it. You see, Marvin Hagler was slagging me off, so I said that and, all of a sudden, everybody’s jumped up and they’re on the phone. It’s the way the press built it up. That’s the problem.”

Battle commenced and Hagler cut Alan’s left cheek early in the first round with his razor sharp right jab. In the second, Alan shook Hagler briefly with a right hook and called him in, crying out “Come on!” As Hagler responded, Alan caught him with a right to the chin that buckled Hagler’s knees for a split-second. But, aside from that moment, despite Alan’s game defiance, Hagler ripped into him with wave after wave of ferocious attacks, fists landing with excruciating regularity. Halfway through the third round, Alan’s face was cut to ribbons and the referee stopped the fight.

Hagler dropped to his knees and, as he did so, the first missile flew over the ropes, the start of a spiteful cascade of bottles and beer cans from every direction. Hagler’s cornermen leapt upon him to form a heroic human shield, and the new champion was rushed from the ring under a heavy police escort while the ringside reporters dived for cover. Back in his changing room, Hagler was calm as he praised the policemen who had rescued him and the referee who had stopped the fight as he felt that Alan was unable to see because of his injuries.

Looking back at that bloody night, Alan philosophically declared “I could see. I was getting hurt though. I wasn’t too happy that they stopped it, but I think they probably did me a favour because he couldn’t miss me with a shot. When I think about it now, I should have let them strip me of the title. I’m not saying if I’d have been given a rest I would have beaten him. I wouldn’t have done, I don’t think, but I fancied my chances. If he couldn’t beat Antuofermo and I beat Antuofermo comfortably, then how could he beat me? It doesn’t work like that, but that was my plan. I thought he couldn’t beat me, but he couldn’t miss me. I mean, I was cut in the first round, the second and the third. I couldn’t avoid the man. I don’t think that at any time in my life or in my career, no matter what I decided my tactics would be, there was no way that Alan Minter would ever have beaten Marvin Hagler, and that’s a fact.”

Six months later, Alan was back with a points win over Ernie Singletary at Wembley and, three months after that, he returned to Caesars Palace where he lost a controversial points verdict to Mustafa Hamsho, a Syrian who was based in New York. “I was working in Birmingham and I was out getting drunk. I got a phone call saying I’m fighting an eliminator for the championship of the world against Hamsho, and I took the shot. I was tired. I wasn’t right. I was walking around at 12/13 stone and I had three weeks to get the weight off. In Las Vegas, it’s a dry heat and you can’t sweat. I was dead at the weight, but I won it and they gave it to him.”

Six months later, on 15 September 1981, at the age of 30, Alan stepped through the ropes for the last time to fight 23 year old Tony Sibson for the European middleweight title at Wembley Arena. Sibson stopped Alan in the third round, putting him down twice in the final moments before the referee put an end to it without taking up the count. “After Hamsho, I’ve got to fight Sibson for a title that I’ve won twice. Why do I want to fight for the European title to fight again for the world title, which is governed by Marvin Hagler? I’m getting old now and I’m fighting for titles which I’ve had and vacated, at 30 years of age.”

“Tony Sibson never knocked me out. The referee stopped the fight when I was on the floor. See, when you’re boxing, you train for a fight whether it’s 12 or 15 rounds. I would never look to see what round it was. In Wembley Arena, they had a big blackboard that tells you what round it is. I’m sitting on my stool, I don’t know how many rounds have gone past, and I’ve turned round and I’ve looked at the blackboard and it said ‘Round Three’. I’ve still got nine rounds to go, and I was gutted, demoralised. I’d had enough, and that was it, full-stop.”

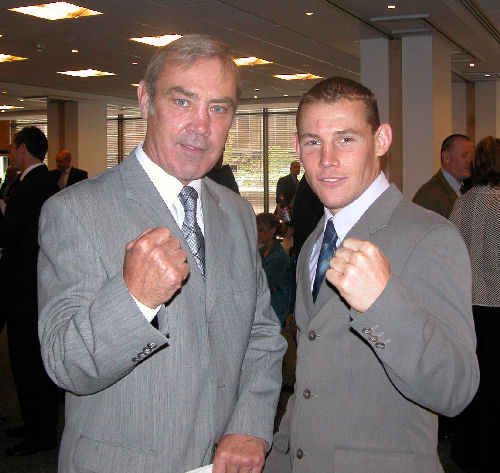

These days, at 50 years old, Alan still looks in great shape, but he was quick to point out “When I go running on my own, I feel like nothing has changed. When I run with Ross, I’m out of it, and I’ve had that kid turn round to me and say ‘Dad, we should have stayed at home, shouldn’t we?’ You don’t think you’ve slowed down, that it’s still there, and it’s not until you’re running with an athlete, someone that’s much younger than you, somebody who’s active, that you realise what a dope you are!”

“Winning the world title was the greatest moment of my life. But, saying that, when I think back to when I was a child watching telly, I remember watching a pro having that Lonsdale Belt wrapped around his waist and thinking ‘That must be the greatest thing that could ever happen to me.’ So, if I’m honest, when I look back at everything that I’ve done, I couldn’t say that one thing tops the other, because everything was an achievement, British, European and world. It was just a lovely moment in time, and you know something? I’ve only got to walk into the Albert Hall or Wembley and, even now, I get dreadful butterflies. It’s the smell. You walk down the steps to where the dressing rooms are and you can smell the same smell that was there when I was boxing. Even driving to Wembley the way I used to go when I was boxing, it’s the same thing. It’s like now, when the air is getting cold and it’s wintery, autumnal, that’s the start of the boxing season.” The blue eyes shine brightly.

Great interview with Alan Minter. Melanie interviews and writes with a passion and flare all of her own.

Great era of boxing Alan will be sadly missed he gave it all to the end.