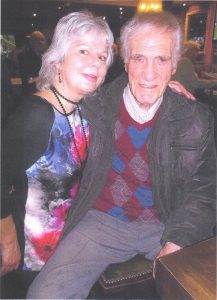

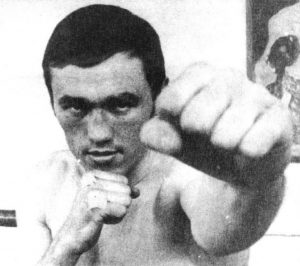

BRIAN HUDSON (Former Southern Area lightweight champ and British title contender)

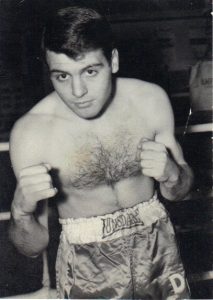

Don’t mess with him (Brian in his boxing days)

He was born in Woodford on 28th December 1945 and christened with the surname Hudspeth. However, he is universally known and respected as Brian Hudson, the name he boxed under as a professional. As with the majority of ex boxers of a certain age, Brian is the possessor of that certain old fashioned calm courtesy that makes one feel instantly comfortable in his presence. His affable nature is underpinned by that matter-of-fact mode of expression that comes naturally to those who feel they have nothing to prove.

“My dad’s name was Tom. He was born in Blackwood in South Wales, and he always kept his Welsh accent. My mum was Florence, but we used to call her Flo. She was born in Woolwich, and then she moved to East Ham. When my mum was 17 years old, she was walking down East Ham High Street when they started dropping bombs on the docks. So she ran all the way home, because they had an Anderson air raid shelter out the back garden. Then her whole family got evacuated to Wales, and that’s how my mum met my dad. My sister, Lorraine, was born in Wales. Then, after the war, they came back to London where me and my younger brother, David, were born.”

“In 1950, I was supposed to go to my first school on a Monday, but it caught fire on the Friday. So they put us on buses to an old prisoner-of-war camp in Chingford where they’d set up another school. Of course, by the time we went there, all the prisoners had gone. But, when we’d get on the bus to come home, I used to see a German helmet on the roof of this building. There’s a golf course there now. I still go by it now and then, and I think back to what it was like. I always tell people I never learned much at school, but I was very good at digging tunnels!”

Brian did not come from a traditional boxing family, but his father was a fan. “My dad had a mate, a Welsh fella called Billy Thomas who turned pro at the age of 16. So my dad liked the fight game and, when I was 11, he introduced me into it. I started off at the Woodford Boxing Club and, when they moved, I went to the Woodford Garden City club where I stayed until I turned pro. The gym was in the Barnardo’s home, and quite a few Bernardo boys used to box.”

“I lost my first five amateur fights. My fifth one was against Jimmy Tibbs. Jimmy was a good schoolboy boxer, and he stopped me in the first round. When I went back to the changing room, a tall fella followed me in with his big Crombie on. He said ‘You’re a little bit short and dumpy for your weight, ain’t you, boy?’ I said ‘Do you think so?’ So he said ‘Yes, when you go home tonight, tell your old man to put some horse shit in your boots,’ and I found out later that it was Jimmy Tibbs’ uncle. After that, I started winning a few and losing a few, but I always liked it. In the end, I had 93 bouts and I won 64. In 1967, I won the ABAs at light-welter, and I boxed for England in the European Championships the same year. It was over in Rome, and I beat a fella from Switzerland. Then I fought Valeri Frolov, the Russian who won the gold, and he beat me on points. But, if I was going to get beat, it was nice to get beat by a gold medallist.”

Upon his return from Italy, at the age of 21, Brian decided to do away with his amateur vest. “Towards the end of my time in the amateurs, Freddie Hill had a gym at York Way above a pub called the Butcher’s Arms, and he trained all Bobby Neill’s boys. There was Alan Rudkin, Frankie Taylor, Peter Cragg, Johnny Pritchett, and I used to spar with all of them. When I turned over, Freddie became my trainer. I always wanted to go pro, and I thought I could get a few bob. All I really wanted to do in life was get a house, where I could say ‘That’s my house that I bought.’ I was married at to Susan when I was 19 and she was 17, and we lived with my in-laws for four years. Susan didn’t mind me boxing when I was younger, although, in the end, she didn’t like it. When I was 23, we got a nice council house, partly because I did well winning the ABAs, so they pushed me up the queue because I put Wanstead & Woodford on the map for sport. But I always wanted my own house, and I got it in the end.”

When Brian turned professional, his manager was Sam Burns, who was the instigator behind the name change. “Sam told me ‘When they send these reports through over the phone, there’s only office boys listening to the results and they don’t know one fighter from another. Hudspeth would be too much of a mouthful. Would you shorten it?’ I said ‘I don’t mind. Do whatever you want to do.’ So he came up with Hudson, and I said ‘Yeah, that would suit me.’”

In September 1967, Brian made his professional debut against Ken Richards at Shoreditch Town Hall. “I felt terrific, especially with it being at Shoreditch. They used to lean over from the balcony and nearly touch you. It was a great place to make my debut, and I stopped him in four rounds. My favourite place to box was Shoreditch, and then York Hall. The Albert Hall was very grand and it was a lovely venue. But, at Shoreditch and York Hall, the crowd was practically on top of you, which was great. A lot of people used to come and watch me box. My dad used to sort all that out. He used to sell a lot of tickets because I was a crowd pleaser. I stopped 15 out of the 18 fighters I beat, but I wasn’t really a heavy puncher. I used to throw a lot of punches, but I don’t think I was aggressive enough sometimes. I had to be hit. In most of my fights, I started off on the floor. I would say I was more of a fighter than a boxer. I’d be bobbing and weaving, getting in and letting them have it. I could always hear the crowd when I was in the ring, and that would urge me on.”

Brian was a natural light-welterweight, but the Board of Control changed the rules and left him in a dilemma. “My natural fighting weight was about 10 stone. In 1969, because I went up the ladder a bit quick, they fixed me up with Vic Andretti, who was British light-welterweight champion. But Vic packed the game up before I got the chance, and the Board did away with the in-between weights. Sam Burns said I should go down to lightweight, because there weren’t so many boys about at lightweight. So I had to lose 5lb before every fight. It doesn’t sound a lot, but I was like a greyhound anyway. So, a week before a fight, I was on a cup and a half of liquid a day, with no bread and no potatoes. Back then, I was working on the Water Board digging the roads up, so I’d get very dehydrated, but it was a good job. We used to get out early in the morning, get the work done as quickly as we could, and in the afternoon I used to shoot up to Battersea and train. It was only a small gym above a pub, but Billy Walker was there, Chris and Kevin Finnegan were there, and it was a terrific atmosphere. Then, after I retired, they brought the light-welterweight division back, which was just my luck!”

In May 1969, Brian won the vacant Southern Area lightweight title against Jackie Lee, stopping the Hoxton southpaw in three rounds at the Hilton in Mayfair. “Winning the Southern Area was terrific. It’s not like winning a British title, but it’s the next best thing. I hit Jackie Lee with a right hand, and I heard Freddie Hill in the background saying ‘He won’t get up,’ and he never made the count. I defended my Southern Area title against Jackie Lee about a year and a half later at Shoreditch, and that time I stopped him in four. They used to say you’ve got to catch a southpaw with a right hand, although I always found it easier catching them with a left hook myself. But Jackie Lee was a terrific boxer.”

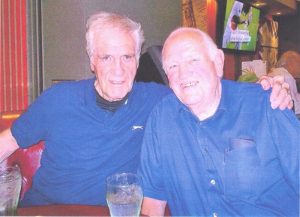

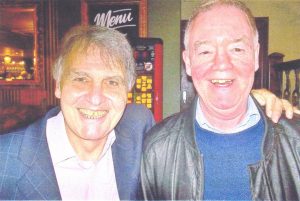

Old opponents and firm friends, Brian and Colin Lake

One of Brian’s old opponents who he is always delighted to see is Colin Lake. They boxed at Shoreditch just before Christmas 1969, and Lake was retired in the seventh because of a cut eye. “Lakey was a crafty boxer. He’d draw you back on the ropes, he had all the old skills, all the old moves, and I was still up and coming really. There was a five year age gap between us and, when you’re young, that’s quite a bit. I don’t think there was much in the fight until he had to retire. It’s great that we see each other regular at the London Ex Boxers Association all these years later and, what’s more, we’re not hitting each other!”

In May 1970, Brian challenged Ken Buchanan for the British lightweight title at the Empire Pool. The outstanding Scot prevailed in the fifth round, but not before Brian had lured the ‘boxer’ into a fight. “He caught me in the first round with a right hand, I think it was, and I was stunned. I went forward, and normally, when you go forward, you don’t get up. I got up and I was a bit dizzy, but I could hear them in my corner shouting ‘Claim him!’ So I claimed him and got through that round, and then I got back into the fight a bit. I’d say that he dominated the opening two rounds. Then I got him at close quarters and I was whacking him, and I think I won the third and fourth rounds. Then he came back with the experience and he knocked me out in the fifth. But Ken Buchanan was so quick. I couldn’t believe how many times he was hitting me. The only thing I can say is that, in his next fight, he won the world title. So, if you’re going to fight someone like that who’s at their best in their career, that’s good for you.”

Brian’s penultimate contest was a swashbuckling upper and downer against Jimmy Anderson at the Albert Hall in February 1971. Brian finished it in the sixth, knocking the former British Light-Welterweight Champion flat on to his back. Anderson rose at the count of nine, but Harry Gibbs stopped the fight. “Now, that was a fight, a proper battle! Before I stopped him, he had me down four or five times. Funnily enough, about 20-odd years ago, I was driving through Enfield and I saw him going round this corner. I said to Susan ‘There’s Jimmy Anderson.’ So we’ve shot round the corner and he went into a phone box. We’ve got out of the car and stood there. When he came out, he was so surprised to see me, and then he told Susan what a good fight we had. He’s a lovely fella and, cor, he could bang!”

Brian stepped through the ropes for the final time in April 1971 at the Grosvenor House Hotel. He was defending his Southern Area title against Willie Reilly, and Brian was retired in round eight. “About three weeks before the fight, I was in Freddie’s gym at Lavender Hill, and I must have hit the bag wrong and my left hand blew right up. Freddie said ‘Don’t do no bag-work, sparring or nothing. Just do general fitness, and the fight will go on.’ On the night of the fight, I’ve gone out and, the first punch I threw, I hit Willie Reilly on the chin and the pain went right up my arm. I came back after the first round and I went ‘Freddie, my left hand has gone.’ Please excuse my language, but he said ‘So use the other fucker!’”

“Me and Willy Reilly were both cut, and the referee didn’t know who to stop. Every time I threw the left hand, the pain was terrible, but I didn’t want to give up. They should have pulled me out after the first round, got my hand better, and then had a return with him, but they never. When I came out of the ring, I said ‘I’m going to pack up, Fred. I’ve had enough.’ I was proper gutted, thinking they were pushing me out when I was injured. So I retired and I was only 25, but I never regretted it. It’s just one of those things that happen in life, and it’s all water under the bridge now.”

“After I packed up boxing, I went back to Woodford Garden City as a trainer, and I helped out there for about four years. But, by now, I was self-employed working on the building sites, and I was training the boys three nights a week and then going out to shows, so I had to pack the training up and concentrate on my work. A while after I finished at the club, they had a tribute night for me at the Prince Regent and so many boxers turned up. It was a lovely evening. They called me up into the ring and gave me a nice big silver plate. Then they’ve only brought out Ken Buchanan! He travelled all the way from Scotland just to be there. I couldn’t believe it when he walked in, and it was terrific to see him again. It was around that time that I joined the London Ex Boxers Association and, in all these years, I’ve always tried my best never to miss a meeting on the first Sunday morning of the month. I love seeing all the old fighters and people I know. Sometimes, I have fellas come up to me and they’ve turned up there just to see me, and they end up joining the organisation, which is lovely. It’s the camaraderie, that’s what it is, all of us friends together.”