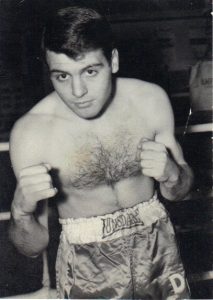

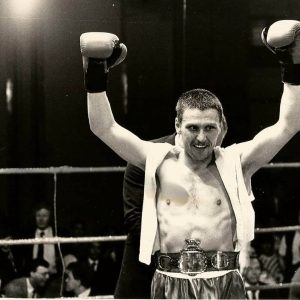

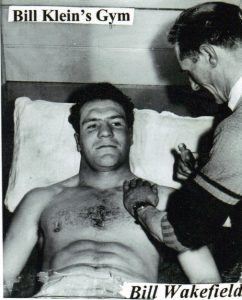

JOE CRICKMAR (Stepney heavyweight from the 1950s)

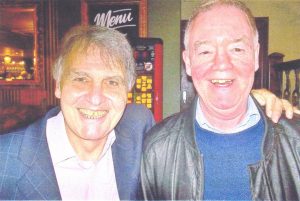

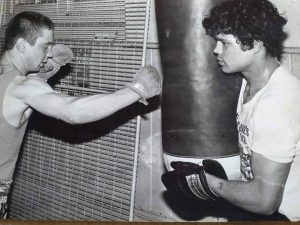

Joe with trainer, Bill Wakefield

Joe Crickmar is a much loved regular at the London Ex Boxers Association (LEBA) meetings which take place on the first Sunday morning of every month at a pub in Old Street. With his craggy good looks and silver hair, together with his warm character and quiet wisdom, Joe could effortlessly put one in mind of an actor, or maybe a vicar. As a boxer, he fought the best British heavyweights of his era, and he held his ground admirably with them all. Born in Stepney on 4th January 1930, Joe’s fascination with boxing came to fruition in 1947. “I first got into boxing when I was 17. I went to the Stepney Institute, initially for carpentry lessons. A lot of my friends were there who I knew in school, and they were boxing. Johnny Gudge was the trainer at the boxing club. Actually, Johnny went onto become a member of LEBA, and it was him who got me to join the association about 40 years ago. Johnny Gudge was a terrific trainer.”

“I had about ten amateur fights, and then, when I was 18, I went in the army and did my National Service. It was 1st April, the day I joined up, April Fool’s Day! I joined the Royal Engineers as a sapper, working with the bombs. I was stationed in Singapore, and I won the Inter Services Heavyweight Championship at Changi Barracks. I got beat in the Far East Championships by Lance Sergeant Huggins of the Grenadier Guards. Then my sergeant said ‘I’ve matched you in the Amateur Championships of Singapore.’ I went straight into the final, and I beat a big Malay Indian. I knocked him out and I won the Championship at the Happy World in Singapore. During my time in the army, I got made up to a Lance Corporal, and then I got made up to a full Corporal after that.”

“When I travelled over to Singapore it took a month to get there, and when I finished in the army it took a month to come home again. The Empire Windrush took me out there, and the HMS Devonshire brought me back. I went back to the boxing club and I won the London ABA Championships against a fella called Eddie Hearn. I beat Hugh Ferns in the National semi-finals, and I got beat in the finals by a fella called Albert Halsey. That was in 1951. I can’t remember exactly how many amateur fights I had, to be honest, but I know I had a lot.”

“Then, when I was 22, I turned professional. I used to idolise Freddie Mills, and he used to come round my house to try and sign me up with Nat Sellers, but I’d already said to Wag Wakefield that I’d go to him, so that’s what I did, and my trainer was his brother, Bill. They looked after me all right. When I was boxing, I used to model myself on Freddie Mills’ left hook and Joe Louis’ left jab. Bill Wakefield used to say ‘Punch through them, not at them.’”

“My last amateur fight was a win against Dinny Powell. Then, funnily enough, in September 1952, I had my professional debut against Dinny, at Wembley Town Hall, and I beat him on points. I also fought Dinny’s brother, Nosher, later in my career at Harringay. Before I boxed Nosher, I’d just had a hernia operation and my spring wasn’t in my feet the way it usually was. Anyway, I got Nosher in a corner in a clinch, and he had his tongue out. I caught him with a right uppercut and he nearly bit his tongue off! The bell went, and he won the fight on points. If that had been a little bit earlier in the round, I would have beat him. Nosher had to have five stitches in his tongue after that.”

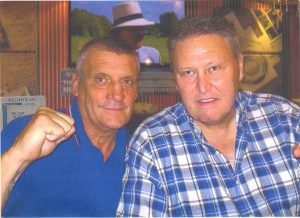

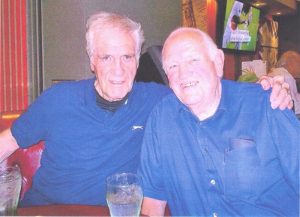

The boxing fraternity moves in mysterious ways, and it was a random conversation between fellow LEBA member, Ivor ‘The Engine’ Jones, and one of his workmates that resulted in Joe being visited last year by a real blast from his past. Ivor’s colleague said he knew an ex-fighter from the 50s named Mick Cowan, who had boxed a man named Joe Crickmar, and you can guess the rest. It had been 60 years since these two onetime warriors had met, which was when they boxed as professionals at the Royal Albert Hall. So Joe had the surprise of his life when, out of the blue, Mick came strolling through the door of a LEBA meeting to find him.

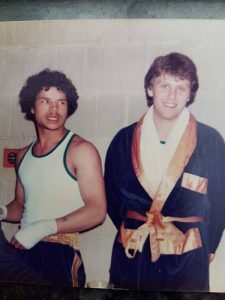

Old opponents, Joe with Mick Cowan

“I boxed Mick Cowan twice as an amateur, and I got the decision against him both times. Then we boxed as pros in April 1953, and I won that one on points as well. Then, after we boxed, he came over to my house in Stepney Green twice to see me, and both times he missed me because I was out working. So the first time I saw him after all these years was when he found out about LEBA because of Ivor. He came all the way from Battle in Hastings to see me, and now he’s one of our members. Mick was a good fighter. I was frightened of his left hand, because he had a good left hand. In fact, it took me all my time to get out of the way of his left hand. He had a better left hand than Joe Erskine!”

“I boxed Joe Bygraves three times, and I stopped him twice. The first time was in June 1953 at White City. It was one of Jack Solomons’ competitions, and they were picking the names of the boxers out to box each other. They said “Joe Bygraves will fight”, and they all went quiet in the dressing room, and then they said “Joe Crickmar”, and they all started talking. We got in the ring and Bygraves came out in the first round, banging and banging, and I was covering up. The second round I let go with a left hand, right hand, left hook, and he was on the floor. He was completely knocked out, and his handler said afterwards that it was because the sun got in his eyes. So I had a return with him up in Liverpool five or six weeks later, and I knocked him out in the fifth round. My wife, Rose, wrote to the paper and asked, ‘If the sun got in his eyes at White City, did the fog get in his eyes at Liverpool?’”

“The first time I saw Rose was when I was doing demolition work for my dad. I used to work for my dad as a builder and we used to do work down her street on the bomb damage, and I used to see her then. We got married in 1953, and we got a letter from the Queen, because it was the same year as the Coronation. We received a photograph of the Queen and a big congratulations card, and we’ve still got that on the sideboard.”

Joe was the first man to beat Derbyshire tough-guy, Peter Bates, in 1954. “I boxed Peter Bates up in Birmingham. Rose came to see that. She was at ringside. I beat him on points, but he did put me down in the last round. I got up straightaway, and then the bell went, and the local paper said ‘Crickmar saved by the bell’, but I beat him on points easy. That was the first time Rose came to watch me box, and the last time.”

“I boxed Joe Erskine in February 1955 at the baths in Leicester, and he won it on points. When Joe wrote his life story in the Daily Telegraph, he said ‘I boxed Joe Crickmar. I beat him then, but I’d like to fight him again to make sure I’d learnt what he had taught me.’ Joe Erskine said that, and I’ve got in black and white. So that was nice. A month later, I boxed Henry Cooper at Earls Court. He stopped me in five rounds. I wasn’t as fit really as I was when I fought Erskine, or anybody else like that. In the fifth round, he cut my eye and the referee stopped it. I had to have eight stitches in my right eye. But I kept getting cut eyes all the time, like Cooper. We were the same like that, because we both had very prominent eyebrows.”

“My last but one fight was against Albert Scott, the South African Champion. That was at Belle Vue, Manchester, and he cut my eye in the fifth round. Then, in my last fight against Ron Redrup, I got cut again. Wag Wakefield used to say ‘Your eyes are your life,’ and I was getting too many cut eyes. In the end, that’s why I turned it in, and also because my wife wanted me to as well.”

“The thing I loved most about boxing was the fitness. I used to love being fit! I was running over the park every morning. I’d go to the gym every night straight from work. It was nice, and I loved all the people as well. It was really lovely. But retirement didn’t affect me at all. I was a jobbing builder, and I just went to work to earn a crust of bread. I’ve got three brothers, Reggie, Ronnie and Kenny. We were all in the building trade with our father, and we were all happy together.”

These days, Joe is well-known at our LEBA gatherings for keeping us all in the picture with his excellent photograph books, which are made of clipped photos from old editions of the Boxing News. “When I first started coming to LEBA years ago, some people used to show you little photos, and I got an interest in it. So I’ve been doing that for many years now. What I look forward to most about our meetings is meeting up with all the boxers. They all come up to me to talk to me. They really make you feel like you’re a somebody, and it’s lovely.”

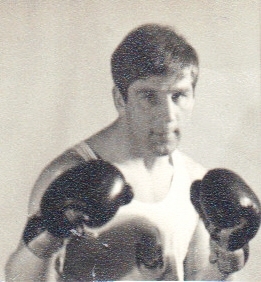

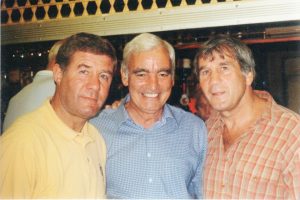

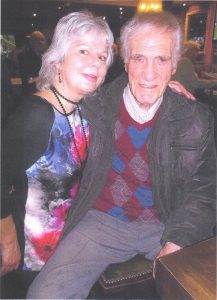

Joe with the Author at a LEBA meeting.