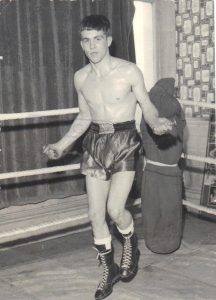

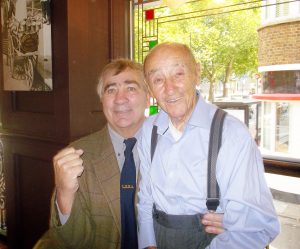

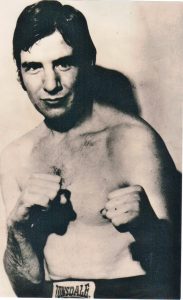

PAT THOMPSON (Former Central Area light-heavyweight champion)

The affable assassin.

His friends call him Killer, but one would be hard pushed to encounter a more amicable assassin than Pat Thompson. When he speaks about what boxing has meant to him throughout his life, his face lights up with boyish enthusiasm. He was born in Merseyside and his formative years were shaped by the fact that Liverpool was still recovering from the aftereffects of the Blitz, not that the lingering war damage prevented Pat and his chums from having fun. “In the street where I lived, some of the houses were bombed, but they just hadn’t had time to knock them down and rebuild them. We used to play in them, trying to catch pigeons and all that. There was one particular street called Reading Street and there were all different landings and, at the back of them, people used to play dice and crap games, and everything was good.”

“I didn’t come from a traditional boxing family. There was my mam and dad, and my three brothers and three sisters. One of my brothers boxed, but that was about it. They did an interview with me years ago, and I’ve still got the tape somewhere. They introduced my mother and they asked her ‘What do you think when your son is boxing and he’s getting hurt and getting battered?’ My mam turned round and said ‘He’s big enough to batter them back!'”

“In the neighbourhood, all the kids were boxing. I used to read about these fellas being good boxers, and the first club I ever joined was the Maple Leaf, but I wasn’t there for very long. Then I joined the Liverpool Transport Club. But, with me being a big lad, I was always a bit big to fight the other kids, so I only had a few amateur fights, about 15 or 20. Having said that, I boxed for England and I won a silver medal in the Multi Nations tournament in Denmark, because I was good, see. I got to the final and I got beat by a guy, and I can’t think of his name now, but he came in with a big Viking hat on him! He was a giant and I suppose I was maybe a bit scared of him, instead of not worrying about him. I went the three rounds with him, but I was grabbing and holding because he was a lot bigger and heavier than me. But I won the silver medal anyway.”

“I joined the Merchant Navy when I was 15. I went into the sea school and they used to have boxing matches every month, and I used to win all the time. Then, after about three months, I went back to Liverpool to get on a ship. I was on all sorts of ships, cargo boats, iron ore boats, passenger ships and tankers, and I was in the Merchant Navy for seven years. I’ll always remember my first trip. I was only 15, turning 16, and we went to Montreal. It took us about a week to get there, and I remember coming off the ship and thinking ‘Blimey, they’ve got pigeons here!’ I didn’t realise that there were pigeons all over the world.”

“I was always training on the ships. When I was on the deck on lookout, when I was supposed to be looking for ships, I’d be shadowboxing all the time to pass the time away. One of the last ships I was on was the Empress of Canada, which used to cruise all around the Caribbean. All the American tourists would be on the ship and we’d put boxing shows on for them, and then we’d go round with the bucket and collect all the dollars. We’d have a share out and we’d all get drunk, and then we used to get fined a day’s pay because we all had hangovers. But it was great. I loved it! It was just wonderful to be with all your mates and we’d box one another, but then we’d be the best of mates after the fight, so it was lovely.”

“I first came down to London with Pat Dwyer. I was going to go back to sea, but Pat said ‘Come down to London and see how you get on down there.’ When I first came to London, we were living in a little hotel in Finsbury Park and then, when Pat went back to Liverpool, I was on my own. Sometimes, you’d come back to the hotel, and there’d be three beds in the room and the landlord used to rent out one of the beds without telling you. So you’d come home and you didn’t know who was there, but we got by.”

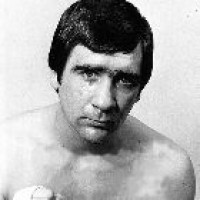

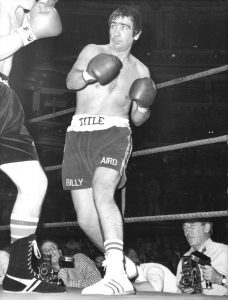

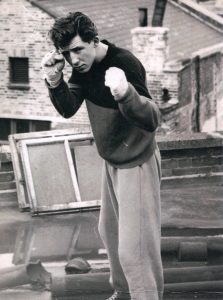

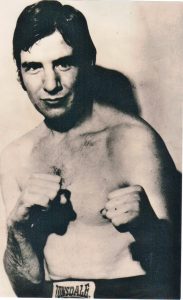

Boxing out of Islington, Pat amassed a record of 72 fights, with 38 wins, 29 losses and five draws in a career that lasted from 1972 to 1977. He regularly fluctuated between light-heavy and heavyweight, and it was all the same to him. “When I turned professional, Ernie Fossey was my manager. In those days, if Ernie said to me ‘You’re fighting King Kong tomorrow,’ I’d have boxed him, because I knew Ernie wouldn’t have me hurt. He really was a good manager and he was a lovely fella. We had such a great time in the gym. We boxed all over the country and we never stopped laughing. To be honest, I was an average fighter, an ordinary guy, an eight round fighter, but I was always happy. I’d fight anybody, and I was always in the gym.”

“I lost my first professional fight on points over six rounds in Manchester. That was against a guy called Terry Armstrong, and I’ll always remember that fight. It’s your first fight with no vest on, and it’s funny the things that go through your head. Then, a few weeks later, I boxed Billy Brooks in London and I stopped him in one round. Throughout my career, I won quite a few and I lost quite a few, but I never really got hurt by anybody.” Pat actually boxed the above mentioned Terry Armstrong six times in total, the final of which provided the setting for the jewel in his career crown, the Central Area light-heavyweight title. He took the vacant belt from the Mancunian on 1st April 1976. The contest took place at the Adelphi Hotel in Merseyside, and Pat made sure that he was no April fool that night. “It was like being king of the country! I loved it, coming home with the belt and showing my mam and dad, and I was made up. I thought I was going to be world champion. I felt like a world champion.”

“When I defended my Central Area title, I boxed a fella called Alex Penarski at the Liverpool Stadium and everyone thought I’d won the fight, but they gave the decision to him. John Conteh was fighting Len Hutchins the same night and Jerry Quarry came over to Liverpool to commentate, and the show was on the telly in America. A lot of my family lived in America, so they saw me box and I’ll always remember what Jerry Quarry said about me. He said ‘This kid has got the greatest smile I’ve ever seen.'”

Throughout the five and a year time-span of Pat’s career, he boxed an average of once a month, often getting the call at short notice. “We used to go to the Noble Art Gym in Haverstock Hill on a Sunday morning and train. I’ll always remember this one time when I came out of the gym and I had nothing going on, so I went and had a pint with the fellas next-door. Then, when I got back to my house, Ernie Fossey called and said ‘Pat, you’re boxing tonight.’ Anyway, I boxed that night and, if I remember it right, I stopped the fella. I don’t know how I done it, but I did! But, even though I was a sort of ‘have gloves, will travel’ boxer, I could sell as many tickets as any of the Londoners, because I had a good name and I was with the right people, like Ernie Fossey.”

“Me and Billy Aird used to spar with each other all the time, and we did used to get up to a bit of mischief. I’ll tell you a little story about big Bill. We were in the Isle of Wight. We used to have a free holiday out of it, because we’d go and spar with the kids over there. Billy had a title fight coming up, and I said ‘Listen, Bill, don’t spar with them little kids because they don’t know what they’re doing. They’ll come and smack you, because they’re only young kids.’ Bill said ‘No, I’ll be all right,’ and this little kid went BOSH and he cut Billy’s eye, so Billy had to cancel his fight. I couldn’t stop laughing! But me and Bill, we always had great times and we were laughing all the time.”

“All through my boxing career, I laughed. Sometimes, you’d have hard fights, but it was the good company that I liked. I loved the camaraderie with the boxers and the banter. I never got into much trouble, because boxing gave me discipline. Every single fella I boxed, I’d have boxed every one of them again. They were all good fellas. Even if you get beat, you still like one another. You stand together. I had some great fights with Johnny Wall from Shoreditch. I boxed him three times. I won one, lost one and we had a draw, but I thought I got the three of them. Another guy I boxed was Billy Knight. He stopped me in five with a cut eye at the Albert Hall. When he hit me, he hit me so hard that I didn’t know if I was in New York or New Brighton! I was still up for it, but I was glad I got stopped with a cut, because he probably would have killed me otherwise!”

Pat’s last ring appearance was a points victory over eight rounds against Theo Josephs at the Norfolk Gardens Hotel in Bradford. “I didn’t know that it was going to be my last one at the time, but I’d had 72 and that’s a lot of fights. Also, I was getting married, so Ernie said ‘You’ll have to retire now.’ To be honest, the signs start showing when you start slowing up a little bit, and you know it’s time to step down and leave it to the young kids coming up. I loved being a boxer and I really missed it, but, when you get older, your timing is just that fraction out. You can see the shot coming, but you just can’t get out of the way and your reflexes start to go. All of a sudden, your opponent is going to throw a left hand at you and you can see it coming, but, before you can get out of the way, it’s got you.”

“Throughout my career, I always worked on the building sites. Sometimes, I’d go to work the day after a fight looking a bit bashed up, and they’d say ‘Hey, good looking!’ Then, when I finished boxing, I became a publican. So I had 72 professional fights, and then I made it 100 by going into the pub! But I loved being a publican. You’re like the Lord Mayor. Everyone knows you. I had different pubs in the East End, and I did that for over 20 years. Then, when the all-day opening came out, the pub game was finished then. After that, I went into the catering game and I’ve been doing that ever since. It’s similar to the pub game because you’re mixing with people all the time, and I love mixing with people.”

“Believe it or not, I’ve never actually stopped training. These days, I’m down the gym about three times a week. I was in the gym a while back and this kid came up to me. I didn’t know who he was. I’d never met him before, but he said ‘I’ve got admiration for you, because it’s inspirational to see you, the way you train.’ When I told him that I’ve been doing it for 50 years, he couldn’t believe it. Obviously, I don’t do sparring, but, apart from that, I do the lot. I do about 12 rounds, shadowboxing, skipping, working on the speed-ball, and I love it. It’s great to still be around the boxing game after all these years, and it makes me feel young.”

Pat still packs a punch.