As an amateur boxer, Mark Lazarus favoured the noble art of defence and ring generalship. As a professional footballer, he was definitely more of a reactionary spirit. In his era, the leather football soaking wet and caked with mud was comparable to a medicine ball, and heavy tactics were entrenched in the game. Mark was a right-winger who took intimidation in his stride and, as a result of his hard-running and fearless approach, together with his instinctive propensity to outwit the fullbacks, cut in and score goals, he became one of the most sought after players in the country.

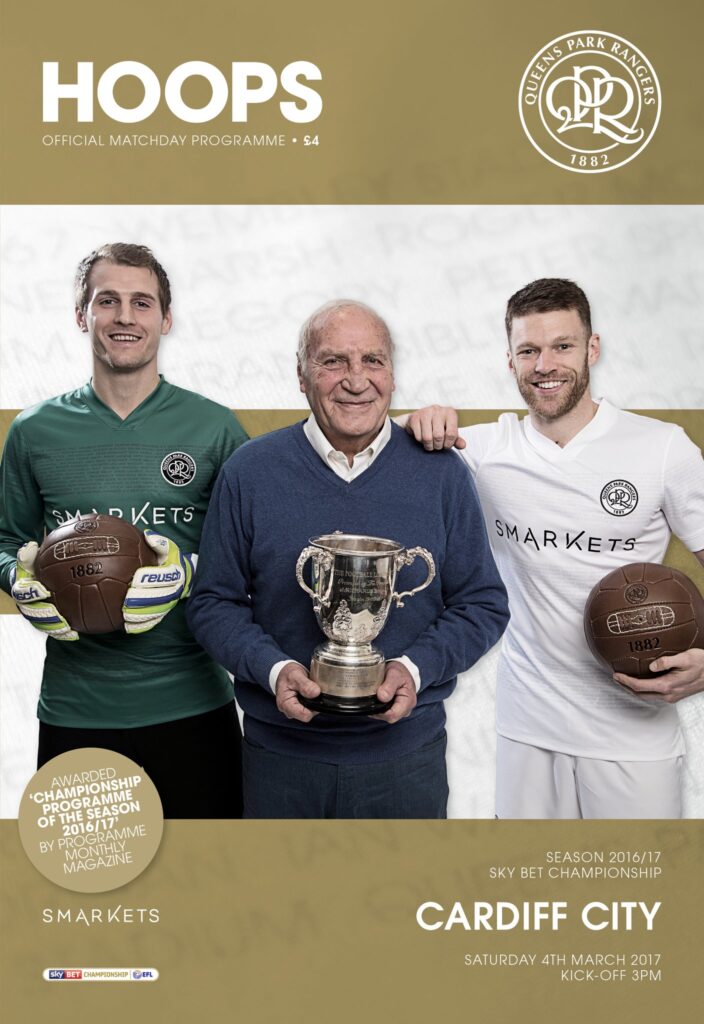

During his 20 year professional career, Mark made 606 appearances in total and scored 151 goals. He played for Leyton Orient, Wolverhampton Wanderers, Brentford and Crystal Palace, but his true love was Queens Park Rangers, for whom he played 206 times and put 76 balls into the back of the net. He completed three separate stints for QPR, during the third of which he scored the winner against West Bromwich Albion in front of a crowd of 100,000 at Wembley, ensuring that Rangers became the first ever Third Division team to win the Football League Cup.

It is now 50 years Mark scored that goal, and he has been in great demand during the celebrations. “West Bromwich Albion were a very, very good First Division side. We were 2-0 down, and we came back and beat them 3-2. Because it’s the 50 year anniversary, I’ve been to QPR and Wembley, I’ve been to a questions and answers session, I’ve been to a new strip fitting, I’ve been to the NFL Awards where we were honoured by the rest of the football community, and that’s all for this occasion. Because I scored the winning goal, I’ve been right at the forefront of it all. It’s been very enjoyable, but quite emotional as well. The whole thing has brought back a lot of old feelings, and football clubs don’t do this often enough. When we go to the boxing meetings, all the boxers go there regularly. Football clubs aren’t like that. They haven’t got the same solidarity with their ex-players. They come, they go, and they’re forgotten. It’s like Tottenham Hotspur or Arsenal, in the past, they’ve won major tournaments, but their ex-players don’t get to go back to the club and meet the players that they played with. It’s not the same as boxing.”

Mark was born on 5th December 1938 in Stepney. He was one of eight boys and five girls, and they were a formidable family. All the boys boxed, most notably Harry and Lew, who boxed professionally and prolifically under the name Lazar, and the girls were also capable combatants. “My brothers in order of age were Harry, David, Eddie, Lew, Mossie, Bobby, me, and Joe. My eldest sister’s name was Rosie. Then came Rayner, who was Harry’s twin. Then came Carol, then Sarah, and my youngest sister’s name was Betty. My sister, Carol, was a right tearaway. She was the best fighter in the boys’ school!”

When Mark was six years old, the Lazarus family moved to Chadwell Heath. “That was in 1945, just after the war finished, and Essex was very different for us coming from the East End. You’d hardly see a car, just horses trotting down the Arterial Road. We were possibly the only Jewish people out that far, and I wouldn’t call it abuse, but we did used to get called a lot of names on our way to and from school. My mother said ‘If anybody calls you anything to do with Jews, you go and sort them out.’ So we used to do that daily. It earned us a reputation that other people got to know, and they were very wary.”

“My dad’s name was Isaac, and he was quite interested in boxing, but he didn’t take the same sort of interest as my mum did. My mum was called Martha, and she used to watch me play all the time. She wouldn’t miss a game, and she was the same with Lew and Harry. She was at all their fights. My mum was a very, very proud woman of all her children. In my house, when we got up in the morning and we were downstairs chatting, it wasn’t ‘How did Arsenal, Tottenham or Chelsea get on yesterday?’ It was ‘How did Sugar Ray Robinson get on?’ We’d talk about Randolph Turpin, Freddie Mills, Bruce Woodcock and Joe Baksi. There was never any football spoken in my house. It was all boxing. I enjoyed playing football at school and things like that, but I didn’t know anything about football or football players.”

“I used to go with my brother, Lew, when he was training at Jack Solomons’ gym in Windmill Street, and I became Snowy Buckingham’s right-hand boy. I’d be the one that would undo the boots of Yolande Pompey, Jake Tuli, Alex Buxton and Henry Cooper. I used to get their skipping ropes for them. I used to help them on with their gloves, and Jack Solomons used to order me around; ‘Go and sit on his legs while he does his press-ups,’ and things like that. I helped with Terry Downes as well, who’s finished up a very good mate of mine, and I went all over the show with Sammy McCarthy.”

“I boxed for three different clubs, Dagenham Trades, Lawnsway and Stepney & St George’s. I didn’t have that many fights, but I never got beat. I boxed at Mile End Baths against a fella, I think his name was Burke, who was the London Federation Boys’ Champion, and I boxed the London Schoolboy Champion who boxed against the Golden Gloves Team from America. I think I was a better boxer than I was a footballer and I could have turned to boxing quite easy, but I was playing football quite a bit and a lot of clubs wanted me to sign for them. When I signed for Leyton Orient as a professional, the Amateur Boxing Association stopped me from boxing. So I think I took the right step.”

“I was in the same Sunday team as Jimmy Greaves, and we played alongside each other on the district side as well. Jimmy and I were the best of friends, even down to coming home and having what we had to eat at the time and going to the pictures in the afternoon. In them days, I was 14 and Jimmy was 13, and he really took hold of the tails of my shirt and followed me around everywhere.”

When Mark was 15 years old, he joined Wingate Football Club, which was an all Jewish side. “When I was playing football, amateurs never got paid, and there was the old saying that you’d find a couple of quid in your boot after the game. I was playing for the Fulham youth team at the time, and Wingate offered me more than a couple of quid to play for them. So it was nothing to do with religion or anything like that. It was strictly all down to money. Bearing in mind that it’s a long time ago now, I can’t remember all of the names, but Frankie Vaughan was on the Wingate team, and I remember Sam Soraf’s nephew, Lenny, played for us as a centre forward.”

In 1957, Leyton Orient manager, Alec Stock, spotted Mark’s talent and signed him up. “I played my first game for Leyton Orient just before I went in the army to do my National Service. I was in the Royal Artillery, and I hated every minute of it. Bearing in mind I’d just turned pro as a footballer at the age of 19, they took two years of my life, which was just really starting. All of a sudden, I was taken away from that environment to become a soldier, which I couldn’t handle either. I was posted at Woolwich, which was just across the water. Every Saturday when I played for Orient, all I had to do was get on the ferry, so that was no hardship. The hardship of it was being in the army itself.”

“While I was in the army, Alec Stock moved from Leyton Orient to Queens Park Rangers. I still played for Orient right up until I got demobbed in 1960, and the new manager there, Les Gore, told me quite frankly that he didn’t think I had a career left in me, but Alec Stock did and he wanted me to go to QPR, and that was the story of how I went over to Rangers.”

“I wouldn’t say I was an aggressive player, but I was retaliatory. If someone kicked me, I wanted to kick them back. If they insulted me in any way, I was prone to knock them down. I stood up for myself. The word was that most of the wingers were frightened of certain fullbacks in my day. But I got in where it hurt, and the fullbacks and defenders knew that they wouldn’t be able to kick me or shove me around. I’d go past a fullback and he’d say ‘You go past me again and I’ll break your legs,’ and I used to just laugh at them. They were more or less the same size as me, some of them bigger, some of them nuttier, and some of them older. Sometimes, they came down the ranks from the First Division, and they weren’t as quick or as good as they were, so they reverted to kicking you instead. I was brought up with football as a contact sport. Today, if you touch anybody, the referee blows for a foul on you. I’d have been sent off every game if I was playing today.”

“I never asked for a transfer from Queens Park Rangers. I was the top dog there, I loved it and they didn’t want me to go. But other clubs were coming after me, and Wolverhampton Wanderers was the top team in the country. They were as big as Manchester United are today. Nobody wanted to refuse to go to Wolverhampton Wanderers in them days, so I signed with them for a record fee at the time of £27,500. But I was never happy at Wolverhampton. There were personality clashes with Stan Cullis, who was the manager at Wolves at the time. I never agreed to live in Wolverhampton. When I signed for them, he promised me that I wouldn’t have to. Once I’d signed, he went back on his word and kept telling me to come up there. The whole thing really was a mistake. Stan Cullis was a sergeant major in the army and he produced that attitude as a manager. He was one of those types of people that I just couldn’t get on with, so I asked to get away.”

“Alec Stock, who loved me to pieces, as a player that is, had no hesitancy in bringing me back to Queens Park Rangers, and it was like I’d come home. I got a very good ovation from the fans when I went back, and I carried on where I’d left off. I used to enjoy my football, and I suppose I was a character. I used to give them a little bit of showmanship. I used to do a lap of honour once I scored a goal, and I used to shake people’s hands on the touchline. In them days, we made ourselves accessible to the fans. We used to travel to matches with them on the train and spend time with them at the supporters’ club, and they enjoyed it as much as we did.”

In 1964, Mark was sold again, this time to Brentford, where he spent two years, made 62 appearances and scored 20 goals, before he returned to QPR for the final time. He set a record for the same player returning to the same side and, on 4th March 1967, in that hallowed Cup Final against West Bromwich Albion, Mark scored the winning goal in the 81st minute. “People always ask me what it felt like to score at Wembley, but it doesn’t register with you at the time. We were professional people and things happen in a split second. I took my chance, I shot the ball into the back of the net, and it just happened to be the winning goal. So that’s more significant than, say, Roger Morgan who scored the first goal or Rodney Marsh who scored the second goal. When you score the winning goal, there’s much more to it. Being a winger, if someone else is in a better position to score, then you give him the chance to score. Although I got a lot of pleasure out of laying on goals for other people, it’s not the same feeling as scoring yourself.”

In 1967, Mark became a wanted man again, this time by the manager of Crystal Palace, Bert Head, who was convinced that Mark was the key player to achieving promotion. Mark played for Palace for two years, and they were indeed promoted to the First Division for the first time. “Towards the end of my career, before I went to Crystal Palace, there was Reading and there was Luton Town who were pushing for promotion as well. Both these teams came to get me, because they knew that I’d get them there. Then, when I left Crystal Palace, I went back to Leyton Orient and they were promoted to the Second Division. I got promotion with three teams on the trot. But I’d had enough by then. I had a transport business running while I was at Orient, and I was a bad trainer to begin with. After 20 years, I didn’t like the thought of getting up in the morning and going training, running round pitches and things like that.”

Having left major league football, Mark finished his career back where he began, at Wingate Football Club, an outcome which suited him down to the ground. “I was at the end of my career and Wingate said ‘We’ll give you a few quid to come and play for us.’ So I just accepted that. It was nice to get back there, and I was only too pleased to play for them again. They said ‘You don’t have to come training. All we want you to do is play for us on a Saturday, and we’ll give you so much a game.’ Seeing as I wasn’t doing anything, I thought it was the perfect thing for me.”

“When you’ve done what I’ve done, it’s been mainly for money. It hasn’t been for the love of the game, or anything like that. But, when I was playing in the First Division with Wolverhampton, money never came into it then. I took a big drop in wages to go back to QPR, because I knew I’d be happy there. I had a love affair with QPR, and I had a very good relationship with the fans, but I also had a very good association with the fans at Brentford. It was the same when I was at Crystal Palace and Leyton Orient. So I wasn’t money orientated all my life.”

Mark has been a regular at the London Ex Boxers Association for the best part of 20 years, and he is proud to belong. “I became a member of LEBA when the meetings were being held at King’s Cross. I get a lot of pleasure out of seeing my idols, like Sammy McCarthy and Johnny Pritchett and, of course, it’s just the whole comradeship of it all. I don’t go to a synagogue, but, if I was to go, I’d sooner go to one like LEBA, because I think it’s just a lovely morning.”